With the news that events in Germany have been cancelled until at least October 2020 and events with capacities over 5000 are banned in Ireland until the end of August, industry professionals are looking to each other and news articles to find some indication of how our industry will be impacted once these restrictions are lifted. Just as our flying experience changed post 9/11 when we were unable to pack liquids over 100ml into hand luggage, events will change, but how?

Starting with academic articles, I’m looking into research on the societal impact on human lives after previous pandemics. I want to understand if there is any evidence of how places of mass gatherings changed, if at all, afterwards. I have just begun and came across newspaper articles on film theatres in the US during the pandemic.

Some of what I read struck me and I share this with you now as it may be of interest.

There were two waves, and social distancing works

Firstly and most notably, there were two waves of the Spanish flu, with the first wave leaving a relatively low mortality rate. The second wave, beginning August 1918 and lasting into 1919, caused devastation. (Killingray, 2003).

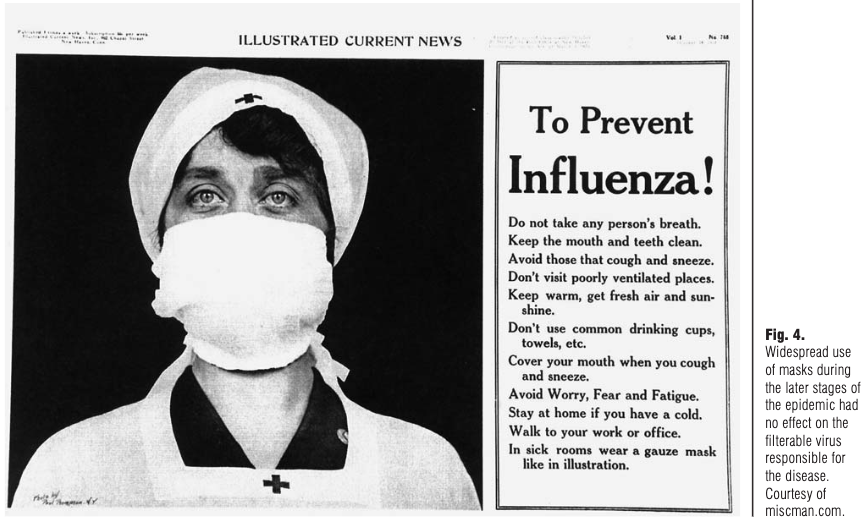

As the advert below indicates, the Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPI) strategy used in 1918 is similar to ours today. The development of Social Distancing as a strategy in the US is outlined in an article in the New York Times, wherein the government ramped up preparation in response to the threat of avian/bird flu H5N1. This triggered studies into the 1918 Spanish flu which both concluded that cities which activated aggressive social distancing measures including the closing of schools, places of mass gatherings, isolation and quarantine; were ones with the lowest overall death toll (Hatchett et al 2007, Markel et al 2007). Furthermore, a study into social network modelling indicated that closing schools and keeping age classes at home proved effective in mitigating progression of pandemic influenza (Glass et al, 2006)

In short, social distancing works and is a key factor in dealing with a pandemic.

Glimpse of the pandemic in the US

Below is a snippet of a public health advert in a US newspaper during the 1918 pandemic. Before being ordered to close their doors, theatres brought in measures such as mask-wearing, with some incorporating it due to fear of being ‘mask slackers’. I find this interesting as it may be a point of further investigation regarding social identity in conforming to social expectations. Other measures included staggered seating and some venues closed altogether due to low audience numbers in fear of catching the virus. In some cities, such as Des Moines, theatres were allowed to remain open but operate at half capacity using alternate rows.

Implementing social distancing was not a consistent process across cities as depicted in this article about Michigan’s Health Board meeting on 19 October 1918;

“Dr. Inches and the Detroit doctors bitterly fought against closing the theatres, arguing that keeping them open did more good than harm not only because of their latest ventilating systems, but because of their educational value.“SOURCE: KOSZARSKI (2005)

After the ban

Many theatres closed and others revived after the ban was lifted, such as in Boston (then lost out to good weather):

“Following the reopening of the motion picture houses after a three-weeks’ closing because of the grip epidemic there was a record breaking attendance. Every manager reported large audiences with a prospect of one of the best seasons in years. Then the weather man stepped in with some of the warmest October days known in years, and after the depression of the epidemic, people flooded into the public parks and out-of-door places in preference to attending the theatres.” (16 November 1918)SOURCE: KOSZARSKI (2005)

However, in Wilmington, new life looked bleak for theatres:

“Attendance at the local picture houses has been away below par since reopening, not even keeping up to the hot weather records for attendance. The epidemic is entirely wiped out here, and the only cause to which poor business can be attributed is the fact that many have found that they can enjoy their own fireside of evenings, and have become more or less detached from their habit of attending the movies by the closed period, which extended over four weeks’ time.” (23 November 1918)SOURCE: KOSZARSKI (2005)

The following gives a glimpse to how life resumed post-pandemic:

“The influenza ban was lifted by the Los Angeles Health Board on 2 December. Theatres opened after a darkness of seven weeks, the longest closed period suffered by any city of this size. People are still nervous about crowds, but houses are doing good business.” (14 December 1918)SOURCE: KOSZARSKI (2005)

What lies ahead

Above is but a snippet, and I hope the insight proved useful. I continue to research articles to identify any indications that may prove useful to the events industry as we continue down this untrodden path.

References

Glass, R. J., Glass, L. M., Beyeler, W. E. and Min, H. J. (2006) “Targeted Social Distancing Designs for Pandemic Influenza.” Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(11) pp. 1671–1681.

Hatchett, R. J., Mercher, C. E. and Lipsitch, M. (2007) “Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic,” 104(18) pp. 7582–7587.

Killingray, D. (2003) “A New ‘Imperial Disease’: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-9and its Impact on the British Empire.” Caribbean Quarterly. (Colonialism and Health in the Tropics), 49(4) pp. 30–49.

Koszarski, R. (2005) “Flu season: Moving Picture World reports on pandemic influenza, 1918-19.” Film History: An International Journal, 17(4) pp. 466–485.

Markel, H., Lipman, H. B., Navarro, J. A., Sloan, A., Michalsen, J. R., Stern, A. M. and Cetron, M. S. (2007) “Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Implemented by US Cities During the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic.” JAMA, 298(6).